On Jan. 8, 2011, Marshawn Lynch's 67-yard "Beast Quake" run propelled the 7-9 Seahawks to a stunning upset of the reigning Super Bowl champion Saints. Three years later, the Saints return to Seattle to once again face the Seahawks, this time as underdogs. Here is the story of the greatest run in NFL playoff history.

* * *

It was a broken play.

Marshawn Lynch took the handoff on second-and-10 and ran into a pile of bodies at the line. Watching from the stands behind the southern end zone of then-Qwest Field, I processed the fallout: the Seahawks, the woeful NFC West's lowly playoff representative, would face third-and-long, run a draw play to bleed more time off the clock, and punt. The Saints, reigning Super Bowl champions, would get the ball back with a timeout and the two-minute warning, and erase Seattle's unlikely four-point lead with a game-winning drive.

What happened in the stadium next is the sort of thing that NFL Films molds into the league's mythology.

Except the play wasn't over. Lynch, somehow still on his feet, staggered out of a mass of bodies, a lateral displacement so quick it looked like a video game glitch. His legs churned, accelerating, cannonballing along the right hashmark. Would-be tacklers reached for him and slid to the turf. He hit the open field and we beckoned him toward our end zone with our voices, already hoarse from shouting for three hours. Tracy Porter put his arms on Lynch's shoulder pads, and Lynch swatted him away like a grizzly knocking a coho to a riverbed. Teammates and opponents hustled downfield, closer to us, closer to pandemonium. A final cutback and Lynch was diving into the end zone.

What happened in the stadium next is the sort of thing that NFL Films molds into the league's mythology, a battle-sport fought by giants and replayed in slow-motion to Wagnerian string music.

But I was there, and I'm telling you: the sky ripped open with noise. A roar beyond sound, a physical thing more industrial than human. The earth shook. It really happened.

This is how.

* * *

THE TEAM

The favoritism extended to the NFL's division winners in the playoffs comes under fire every year, but the complaints were never more justified than after the 2010 season. The 7-9 Seahawks hosted a home playoff game against the 11-5 Saints, who were relegated to the 5-seed and a Wild Card berth by the 13-3 Falcons, winners of the NFC South. The Giants and Buccaneers both finished 10-6 that year, and neither team made the playoffs. Three years have passed, and this is still unfair and always will be.

How bad were the Seahawks? Their net point total for the season was -97, third-worst in their own division (the 7-9 Rams and 6-10 49ers finished at -39 and -41). The team had a quarterback controversy between Matt Hasselbeck and Charlie Whitehurst. Their leading receiver was Mike Williams, the infamous draft bust reclaimed by Pete Carroll in his first year as the Seahawks coach.

The 2010 Seahawks remain the only NFL team to play a full season and make the playoffs with a losing record.

According to Football Outsiders' advanced metrics, the only playoff team worse than the 2010 Seahawks was the Rams team of 2004, which made the playoffs as a Wild Card at 8-8 (and promptly defeated the Seahawks for a third time that season). The 2010 Seahawks remain the only NFL team to play a full season and make the playoffs with a losing record.

But the seeds of the NFL's best team during the 2013 regular season had taken root in 2010. Following a disastrous 2009 under Jim Mora, the Seahawks hired Carroll and paired him with new general manager John Schneider, architect of the Packers team that won Super Bowl XLV. In the 2010 draft, Schneider and Carroll used a pair of first-round picks to select left tackle Russell Okung and free safety Earl Thomas, both of whom would be impact rookies. Golden Tate, Walter Thurmond, and Kam Chancellor -- all significant contributors to the team today -- were also rookies in 2010.

But the team's biggest personnel move of 2010 happened a month into the season. The Seahawks gave up a fourth-round pick in 2011 and a fifth-rounder in 2012 to acquire Marshawn Lynch from the Bills. Lynch, drafted 12th overall in 2007, started his career with back-to-back 1,000-yard seasons that lost their luster after run-ins with the law. His driver's license was revoked in June 2008 for a hit-and-run incident, and in March 2009 he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor gun charge, which resulted in a three-game suspension to start the 2009 season. Later that year, Lynch lost the starting job to Fred Jackson. With the Bills' addition of C.J. Spiller in the 2010 draft, Lynch's exit was only a matter of time.

"I had known him growing up, coming through high school and all that," Carroll told ESPN, referring to his time as the coach of USC. "I knew who he was, the style that he ran with. I wanted to see if we could include that into the building of this program."

* * *

THE BEAST

Lynch grew up in Oakland, became a prep sensation for Oakland Tech, then committed to play at Cal -- a 10-minute drive up College Avenue -- where he became the school's all-time leading rusher. He is a folk hero in the East Bay, as memorable for his personality as his skill on the field. This was never more clear than in Cal's win against Washington in 2006, after the Huskies forced overtime with a Hail Mary that sucked the air out of Memorial Stadium. Lynch, playing with two sprained ankles, rushed 21 times for 150 yards and two touchdowns, including the game-winner. He celebrated with a joyride in a commandeered injury cart.

For someone accustomed to a small radius of sunshine and family, Buffalo, perhaps, was not the ideal city to begin his pro career. "I didn't know what to expect. I just knew I was going to New York," Lynch told ESPN's Jeffri Chadiha in a rare interview last year. "I thought I was going to be out there with Jay-Z, and then when I finally landed in Buffalo" -- his voice sank with disappointment -- "aw, man, it was like, slush on the ground. Just finished snowing." He shook his head, recalling the trauma. "I don't know nuthin' about no snow."

Nevertheless, Lynch endeared himself to the community. After Willis McGahee famously dismissed Buffalo's nightlife -- "Can't go out, can't do nothing. There's an Applebee's, a TGI Friday's, and they just got a Dave & Busters" -- Lynch teamed with ESPN's Kenny Mayne in a scripted segment that celebrated the city's chain restaurants. ("I love the ambience, I love the decor," Lynch deadpanned from an Applebee's booth.)

That eccentricity has continued in Seattle, most notably with Lynch's habit of snacking on Skittles between offensive series. And while his on-field potential has been realized -- three 1,200-yard seasons in his three full years in Seattle -- he also faces the possibility of another suspension from the league. Lynch was arrested for DUI in Oakland last summer, and his case will go to trial this offseason. These factors -- the arrests, the braids, his hometown -- make Lynch an easy target for the "thug" stereotype trotted out by columnists and talking heads.

ESPN's Chadiha asked Lynch about that perception last year. His response: "I would like to see them grow up in project housing, being racially profiled growing up, sometimes not having anything to eat, sometimes having to wear the same damn clothes to school for a whole week. And then all of a sudden a big-ass change in they life -- like, they dream come true, to the point where they starting their career at 20 years old, when they still don't know shit -- I would like to see some of the mistakes that they would make."

Perhaps that attitude -- an awareness of the divide between his life and those who talk about him -- is the impetus behind Lynch's media silence. The NFL fined Lynch $50,000 for not talking to reporters all season, a silence only recently broken when he granted reporters 83 seconds of his time after practice.

Seahawks fans responded by setting up a website to raise the money for his fine. The site's creator, Loren Summers, wrote "we don't need his interviews or his thoughts to appreciate the amazing talent he is, and the contribution he makes to our team." (For his part, Lynch has vowed to match the money raised and give it to charity.)

The underlying message: if Lynch would rather his play do the talking, Seahawk fans are more than happy to produce the noise. That much has been clear since his first playoff game.

* * *

THE PLAY

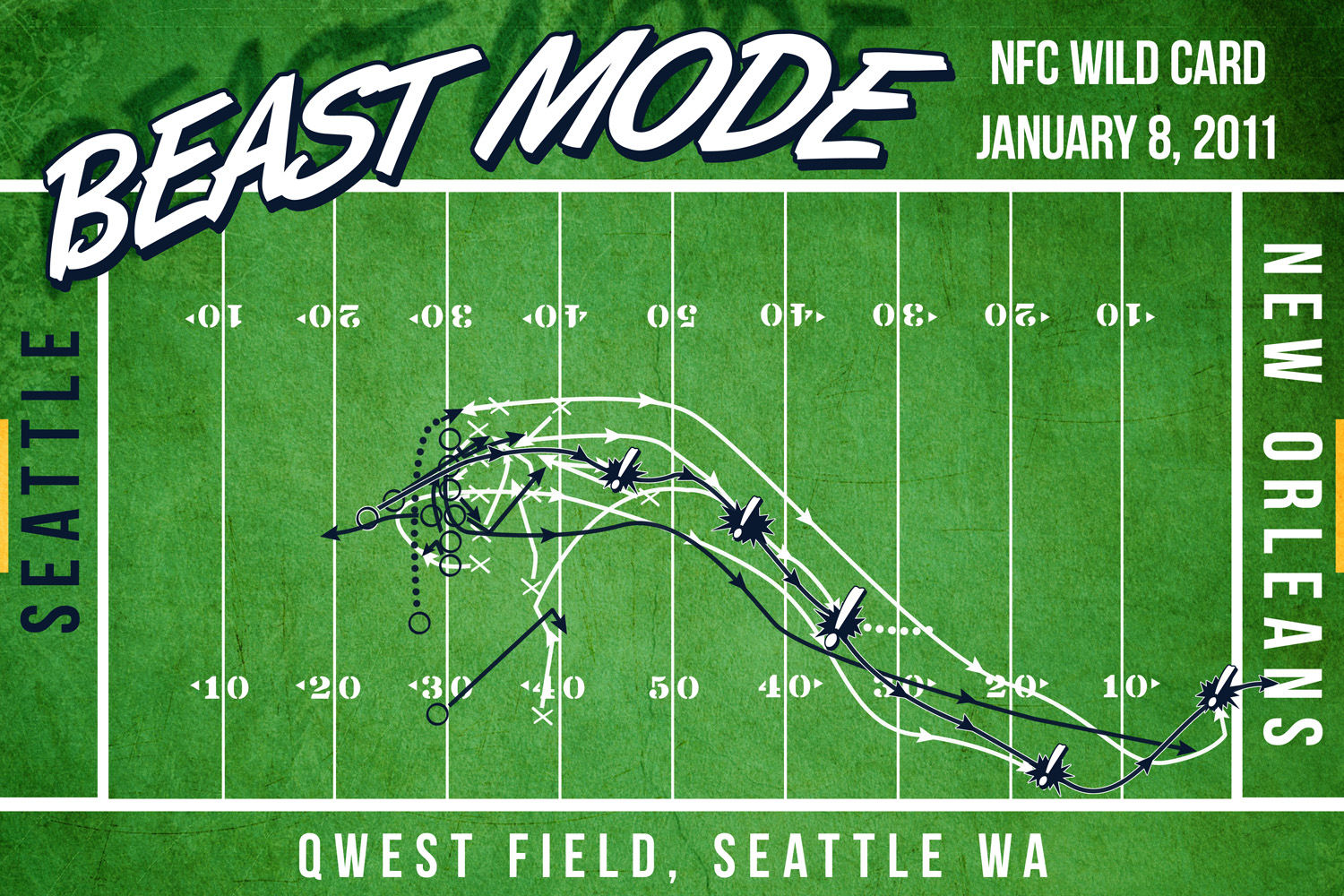

(Artwork by Justin Bopp; purchase a print here)

(Artwork by Justin Bopp; purchase a print here)The run now known as the "Beast Quake" is a play called 17 Power. Essentially, everyone on the offensive line blocks down to the right, except for a pulling guard, who follows the fullback to the left, blocking linebackers and making space for the running back to follow through the frontside gap.

Or, as Lynch put it in an interview with NFL Films, "With Power, you runnin' straight downhill. You know where we comin', and we know where y'all gonna be lined up at. Now you just gotta stop me. I'm saying I'm better than you."

Facing second-and-10 and clinging to a four-point lead with 3:34 remaining against the Saints, the Seahawks are looking to bleed some clock and set up a manageable third down. They line up in an offset I-formation with Lynch and fullback Michael Robinson in the backfield. Tight end John Carlson is lined up outside left tackle Russell Okung, and wide receiver Ben Obomanu motions right to left, settling just outside Carlson. It's a run-heavy look, and the Saints respond by stacking eight men in the tackle box.

After the snap, things go pear-shaped quickly. The pulling guard, Mike Gibson, gets tangled up with Carlson as the two cross paths, leaving linebacker Scott Shanle unblocked as the ball carrier hits the hole. Shanle wraps Lynch up, but Lynch shrugs him off like a particularly heavy coat. (Danny Kelly, who regularly breaks down plays at Field Gulls, SB Nation's Seahawks blog, wrote to me: "Breaking a tackle in the open field is one thing, but running through a tackle like this when you're in a phone booth is a whole different feat.") Lynch slides to the right, where a hole in the line has opened up.

The hole is a result of defensive tackle Sedrick Ellis not containing the backside of the play. At the snap, Ellis -- lined up opposite Gibson and right tackle Sean Locklear -- keeps his eyes in the backfield and stunts over the top of the formation. He correctly guesses the hole that Lynch is going to hit -- only to find himself stacked behind Shanle, unable to make a play.

At this point, Gibson's early collision with Carlson becomes fortuitous: if Gibson had reached the hole to make a block on Shanle, Lynch likely would have found himself in the arms of Ellis. Instead, Shanle's tackle is broken, Ellis is out of position ... and Gibson rights himself and heads into the second level to lay a block on Tracy Porter, who will famously reappear in the play a few seconds later.

From there, it's all Beast Mode. Lynch breaks simultaneous arm tackles from Darren Sharper and Remi Ayodele. Jabari Greer launches himself at Lynch and slides off like a child flailing at his older brother. Porter hustles back into the picture to grab Lynch's shoulders, and Lynch responds with something that's less of a stiff-arm than a judo-like shove -- a cruel application of force that uses Porter's momentum against him and sends him turfward.

Lynch would later elaborate on the famous stiff-arm to NFL Films. "We almost was runnin' at top speed, so any kind of shove right there will throw a man off course. It's just a little baby stiff-arm." He smiles. "Yeah, a little baby stiff-arm."

Marshawn Lynch knows some mean-ass babies.

Lynch, slowed down by delivering the stiff-arm, is still 35 yards from the end zone, and his loss of momentum allows Saints and Seahawks alike to re-enter the play. On the telecast, Mike Mayock praises the hustle of Hasselbeck and Locklear to get downfield, but both narrowly avoid blocking defensive end Alex Brown in the back. Brown dives at Lynch at the sideline, but Lynch sees him coming and keeps his feet from getting tangled up.

"I'm just thinking, ‘What the hell just happened? Did this really just happen?'"

At the 10-yard line, Lynch cuts back to the center of the field. Safety Roman Harper is the last Saint with a chance at Lynch, but left guard Tyler Polumbus -- a 305-pound man who has sprinted 65 yards downfield -- delivers a block that makes Harper's effort fruitless.

Lynch: "I'm just thinking, ‘What the hell just happened? Did this really just happen?'"

It really happened: at least seven New Orleans defenders got their hands on Lynch, and none could tackle him. Future TV replays will avoid the angle that shows it, but Lynch dives into the end zone while grabbing his crotch.

As he told Chadiha, "That was the stamp. The statement. With all that shit, you gotta finish it off somehow."

* * *

THE QUAKE

Lynch, standing in CenturyLink last summer, said, "If you wasn't in this stadium to see it and hear it, I feel you're being shortchanged by watching the video. It was that. Damn. Loud."

Although I was too hoarse to speak above a whisper for two days following the game, I was skeptical of the reports of seismic activity. It seemed overblown, an opportunity for the media to mythologize something that caused the slightest hiccup on hair-trigger instruments.

I called John Vidale, a professor at the University of Washington and the director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network. With the clipped, informational speech patterns of an engineer, Vidale deflated each of my attempts to demystify the Beast Quake.

Is a seismic reading from a CenturyLink crowd common?

"I could find lots of noises from the stadium [throughout the 2010 season], but this one for Marshawn Lynch's run was twice as big as anything else all year from the football stadium. It was a very enthusiastic crowd."

Was this really an earthquake? Like, if someone had been walking by the stadium when it happened, would they have felt it in the ground?

"You'd probably feel the ground vibrate a little bit. I think you could have felt it in the ground if you're within a block or so."

But it wouldn't measure on the Richter scale, right?

"It would probably be the energy of a magnitude-one earthquake; even though the motion was kind of small, it lasted a long time."

Well, shit. That's an earthquake.